Recollecting Walk21 Portugal and Lisbon

By: Görsev Argın Uz, Director of Training and Projects & Local Government Academy

The present is walking, the future needs to be walkable. The Walkability Institute, founded by Brazilian women, encapsulates our modern reality with these words. However, we live in a present shaped by a vision of cities whose future has been imagined with no room for walking. This reality also brings with it a rare historical pursuit: a search for a return to the past. We are striving to transform car-centric cities and prepare them for the future by placing walking back at the center.

The act of walking is one of our most basic behaviors, yet it carries a rich layer of meaning. This is why I was deeply excited about the 24th International Walk21 Conference, which brought together people from around the world who research, work on, and innovate in the field of walking. Walk21 Portugal was held in Lisbon, Portugal, from October 14–18, 2024, and focused on this fundamental question: “How can we develop and implement walking policies and programs to create safer streets, more inclusive communities, and solutions worth walking for?”

At a time when we are drawn to "big" and "innovative" transport projects, even as we acknowledge that walkability is a key solution, Walk21 Portugal urged us to redirect our focus away from such "trendy" initiatives and back to walking and active mobility. It brought together decision-makers, practitioners, academics, and activists from around the world to explore how walking policies are transforming the urban paradigm, shaping people's walking experiences, and contributing to goals of safety, equity, and climate action. The conference also served as a platform to examine the elements of successful national policies, local actions, and transformative projects, while introducing new initiatives in the field, such as the Pan-European Walking Master Plan and tools like the Walkability App.

Organized on behalf of the Government of the Portuguese Republic in collaboration with the Institute of Mobility and Transport, the City of Lisbon, Walk21, and ISCTE, the event turned Lisbon into not just the host city but also a living laboratory of experience. The city shared not only its success stories but also its challenges and dilemmas with participants in a transparent manner. The City of Lisbon further enriched the experience by offering participants access to many of the city’s facilities throughout the conference. For instance, all public transportation was made free of charge for attendees during the event. This approach ensured that not only the physical spaces but also the city’s mobility experience became an integral part of the conference. The event officially began a day early with a Sunday Walk through the streets of central Lisbon, which were closed to vehicular traffic for the day. Accompanied by music and various performances, the walk provided a meaningful start and inspiration for the topics to be discussed during the five-day conference.

Shades of Learning

The conference revolved around four main themes: (1) Inclusivity, (2) Positive Public Space, (3) Climate Imperative, and (4) Good Governance. The event featured a diverse and dynamic format, including plenary sessions, roundtables, pecha kucha presentations, workshops, walkshops, field trips, and interactive sessions during coffee breaks. Additionally, the introduction of “learning labs,” organized for the first time this year, brought an added layer of depth to the conference.

The aim of the learning labs was to explore all aspects of walkability projects—the good, the bad, and the ugly. As the Marmara Municipalities Union (MMU), we participated in the learning lab organized by the Global Designing Cities Initiative (GDCI), titled “Plazas to Streets for People: The Story of Cities Scaling Up a Pop-Up to Citywide Programs.” In this session, we had the opportunity to present the outcomes of the Reclaiming Streets program, implemented by MMU’s Local Government Academy in collaboration with GDCI and Superpool.

The overall structure of the conference centered on networking, knowledge sharing, and fostering collaboration. The energy and sincerity of the Walk21 community were among the most notable aspects of this warm and welcoming atmosphere. The inclusive approach of the Walk21 team—especially Bronwen Thornton, CEO of Walk21 and a MARUF23 speaker, and Jim Walker, Director of Walk21— and participants made networking both enjoyable and highly productive. This friendly and supportive environment helped forge strong connections among participants and encouraged the exchange of ideas. Undoubtedly, the karaoke party during the conference dinner also played a part in creating this lively and warm atmosphere.

This conference was also one of the events where I met the largest number of new people and engaged with a wide range of ideas. The participants came from highly diverse backgrounds, and everyone was both supportive of and curious about each other’s work. There were even two “aliens” at the conference. Offering an external perspective on the use of public spaces and streets in cities, these two "space/space experts" had supposedly traveled from their home planet to study street culture worldwide. Their observations highlighted the conflict between people's enjoyment of streets as walkable spaces and the tension arising from competing demands on limited public space.

I think if we were to look at today's streets from an outsider's perspective and ask the question, "Who owns the street?" we likely wouldn’t like the answer. This kind of external viewpoint highlighted an important truth that was revealed at Walk21: Streets often appear to be "de facto" dedicated to vehicles or specific uses due to ingrained habits. However, these habits are frequently arbitrary and represent outdated patterns that need to be abandoned. This realization serves as a powerful reminder of the urgent need to rethink and transform our streets.

What Have We Learned by Transforming the Streets?

Increasing traffic congestion and declining quality of life across the globe have exposed flaws in urban planning strategies that prioritize private car usage. Over the past decade, this has spurred a global trend to prioritize pedestrians and bring people back to cities. Many organizations are adopting a "step-by-step" approach to transforming the built environment, addressing one street at a time. In this context, the GDCI collaborates with organizations across various sectors and scales to implement street transformation programs in diverse parts of the world. These efforts aim to reclaim urban spaces for people, fostering more accessible, livable, and pedestrian-friendly cities.

In the learning lab session, we participated in at Walk21 Portugal, three organizations came together to share their experiences: GDCI, operating on an international scale; MMU, working on a regional scale; and the City of Milan, implementing projects on a citywide scale. Since its inception, Milan’s Piazze Aperte program has pedestrianized 42 streets and squares, reclaiming a total area of over 28,000 m². Similarly, the Reclaiming Streets program has transformed 15 streets across 5 cities in the Marmara Region, pedestrianizing more than 10,000 m².

In the learning lab, we focused on our experiences from the projects and shared with participants the challenges we encountered at various stages of the programs, as well as the strategies and tactics we employed to address them. We discussed our future plans, including successes and setbacks in community engagement efforts, the analysis of collected data, and ways to institutionalize this data to create safer, more accessible, and more comfortable streets and public spaces.

In the Q&A session following the short presentations, we had the opportunity to openly discuss our failures as well. Specifically, we delved into the challenges and opportunities associated with tactical urbanization approaches when collaborating with strategic actors such as municipalities. These open and constructive discussions offered a valuable foundation for developing more effective solutions in future projects.

Can We Imagine More?

During Walk21 Portugal, we had the opportunity to meet and hear the stories of “street transformers” from around the world. We engaged in discussions about projects of various scales, from school streets and blocks in Tirana to school streets in Turin, Italy; from pedestrianized streets in India to transformed boulevards and highways in Paris. This diversity provided us with a global perspective on street transformation and reinforced the understanding that our local projects are part of a larger, worldwide movement.

Listening to these diverse experiences also inspired us to imagine more. Paul Lecroart from the Paris Metropolitan Region Planning Agency shared compelling examples of major cities transforming their wide highways into green streets. According to Lecroart, this story traces back to the 1950s, a time when the vision for the future of cities was entirely different. Cars were regarded as saviors, accelerating our lives and simplifying daily tasks, and it was widely believed that the cities of the future would be designed around expansive highways for vehicles. However, the flaws in this vision have become increasingly apparent in today's urban landscapes.

Urban life and public life are fundamentally shaped in the spaces between buildings—in streets and squares. However, dedicating these spaces to vehicles and prioritizing them over people deeply undermines public life. As roads are widened and their numbers increase, traffic problems escalate proportionally. Additionally, the climate crisis exacerbates these issues, demanding urgent and effective solutions.

However, successful transformation stories, such as Seoul's renowned Cheonggyecheon restoration project, provide inspiring examples. By dismantling a massive highway, Seoul reclaimed a long-lost stream and transformed the area into a vibrant, breathing public space. Paris is now taking a similar path, making significant strides to reclaim large highway areas for people and nature.

Lecroart's experience demonstrates that it is possible to reimagine cities by learning from the mistakes of the past. Transformations that shift away from a car-centric urban model and prioritize people and public life are not merely dreams—they are achievable realities.

All this made me reflect on what we imagine today about the cities of the future. Perhaps the ideal cities of tomorrow won’t look so futuristic but instead will be composed of public spaces shaped by pedestrians and nature. This vision aligns perfectly with the mission of The Future Design of Streets team, whom I met at Walk21 Portugal. In a brief 20-minute café session titled “Walkable Streets: If We Know the Solutions, Why Can’t We Accelerate Action?” they initiated a short yet profound discussion on this very topic.

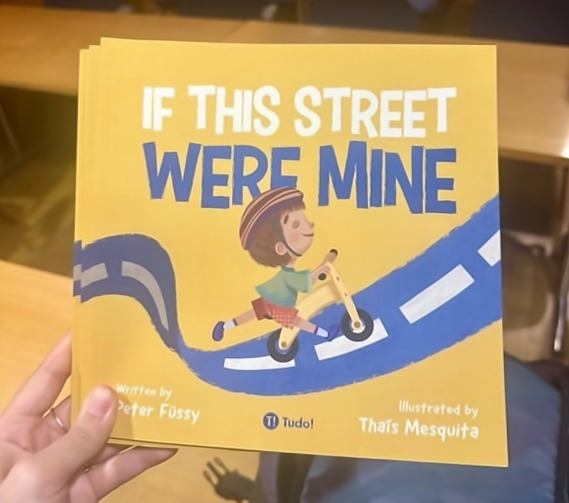

Even children born into today's world have vastly different expectations of streets compared to previous generations. To understand their new perspective and redefine the meaning of streets, we need to rewrite the story of streets. A great example of this approach is Peter Füssy’s children’s book If This Street Were Mine, which encourages both children and adults to view streets in a new light. The book portrays streets not merely as transit spaces but as vibrant living spaces, while redefining the true owners of these spaces.

Walking-led governance plays a crucial role in imagining better cities and turning these dreams into reality. The closing session, featuring women leaders and activists from across the globe, highlighted the pivotal role women play in building walk-oriented cities. Leaders from Portugal, France, Ecuador, Brazil, and Kenya emphasized that only through strong governance can effective policies be developed. These discussions served as a powerful reminder that streets are not merely physical spaces but living spaces at the heart of social transformation. This women-led approach inspired us all to work towards making streets more inclusive, safe, and accessible.

Learning by Walking

One of the most effective methods showcased at Walk21 Portugal was undoubtedly the walkshops, which we also experimented at MARUF23. Talking about walking from the comfort of your seat is not enough, you need to experience it. During the conference, I participated in three different walkshops and a field trip.

The first of these walkshops focused on experiencing the city through the eyes of a child and the caregiver accompanying them. In the workshop, I tried out methods such as stroller inspection and inverted periscope, tools we often use in MMU’s Local Government Academy. Additionally, we used innovative approaches like Identity Lens Cards to understand the city from the perspectives of both a child and a caregiver. These tools helped us identify physical and social barriers within the urban environment while inspiring new ideas for designing public spaces that are more accessible and inclusive.

The second walkshop was a sensory walk organized by the Pedestrians’ Association from Türkiye. During this walk, participants were invited to explore Lisbon using only one sense of their choice. I chose to focus on sounds along the route. At the end of the walk, we completed the experience by sharing our feelings and perceptions with the other participants. As with other sensory walk experiences I’ve participated in, the route—carefully selected by the organizers—remains vividly etched in my memory with its unique details. I was deeply impressed by the differences between what I felt while listening and what I saw. It was particularly enlightening to realize how focusing solely on auditory senses transformed my perception of the spaces around me. Experiences like this reminded me once again of the multilayered nature of walking and how powerful a tool it is for uncovering the many faces of a city. Even through walking alone, it is possible to discover entirely new stories and details about the fabric of an urban environment.

One of the events that impressed me the most was the walkshop titled “Feminism, ‘Poor Things,’ and Lisbon-Night Walk.” This impactful night walk was organized by representatives from three different organizations across three countries: CAMINA (Los Angeles, USA), the Walkability Institute (São Paulo, Brazil), and the CAMINA Center for Pedestrian Mobility Studies (Monterrey, Mexico). The workshop aimed to analyze the city through a gender perspective. It began in a square commonly frequented by immigrants, wound through Lisbon's historic center, and concluded at the Mirador of Santa Luzia.

In this walkshop, which provided a rich foundation for discussion through its references to the movie Poor Things, we were asked to evaluate each public space we passed during the walk using six criteria: signalized, visible, vital, surveyed, equipped, and community. These categories enabled us to perform a comprehensive analysis of how safe, accessible, and functional each space was for its users.

This walkshop helped me grasp the complexity not only of Lisbon's physical spaces but also of the meanings embedded within them. The experience concluded with a powerful message: public spaces must be accessible and safe for everyone, at all hours of the day. This added a new depth to the concept of walkability from a feminist perspective. It also broadened my awareness of both urban design and the profound impact that public spaces have on their users.

During my final field trip, I chose to explore Lisbon's transforming public spaces. Guided by experts from the City of Lisbon, I learned about the dilemma posed by Lisbon's famous Calçada paving stones. Calçada is a historical and iconic element of the city, crafted using traditional methods and unique to Lisbon. These stones are a defining feature of the city’s identity and are used in almost every public space. However, this aesthetic and traditional choice also brings significant challenges.

These stones often lead to injuries due to their uneven structure and slipperiness in wet weather. This issue is particularly significant in Lisbon, which has a large elderly population, making accessibility a serious concern. As the guide pointed out, Lisbon faces a critical dilemma: traditional aesthetics or accessibility? Balancing the creation of safer, more accessible, and functional public spaces with the preservation of tradition and the city’s cultural heritage could be the key to navigating this transformation process.

Lisbon captivated me with its food, pastel de nata, trams, sidewalks, streets, squares, music-filled atmosphere, and miradors offering free enjoyment of breathtaking views. This city is etched in my memory not only for its visual beauty but also for its distinctive features and innovative solutions for walkability.

It was announced that Walk21 will be held in Tirana next year. Tirana defines itself as a child-friendly city, and it seems to be gearing up to share its many stories, both successful and challenging. I strongly encourage you to stay tuned!

Last words...

I returned from Walk21 Portugal with countless ideas and a renewed conviction about what can be achieved to promote walking. Most importantly, I came back with a profound awareness that there are many ways to encourage walking and increase active mobility. When discussing walking and active mobility, we often emphasize the need for courage from decision-makers, and perhaps at times, we hide behind this necessity. However, I was deeply moved by the words of Pedro Homem de Gouveia from POLIS:

“We talk a lot about political courage, but we also need professional courage... We don’t need to be Superman or Superwoman, we just need to do our job.”

This reminded me that taking action is a shared responsibility—it’s not just about good intentions, but a professional duty that demands expertise. Walking and active mobility are not only vital for saving our cities but are also among our most fundamental rights.

Now, it’s time to turn our words into action—in other words, to “walk the talk!”

*Photographs used in this article were taken by the author.